- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

For some there is a paradox in the fact that Bob Jones University, a Christian-fundamentalist institution that bills itself as the bastion of “old-time religion” based on the absolute authority of the Bible, should be a repository for one of the best collections of Catholic art in the United States. In the words of Henry Hope, who first introduced the university’s museum to the public (“The Bob Jones University Collection of Religious Art,” Art Journal XXV, no. 2 (1965–66): 154–162), the spirit of the collection is “more that of the Counter Reformation than of Martin Luther” (162). In this respect, little has changed since Hope (followed by Donald and Kathleen Weil-Garris Posner’s, “More on the Bob Jones University Collection of Religious Art,” Art Journal XXVI, no. 2 [1966–67]: 144-153) reviewed the collection almost forty years ago; the holdings still overwhelmingly salute traditional Catholic religious themes (or Catholic interpretations of Old Testament events and personages). Notwithstanding, new acquisitions and adjustments to attributions have both qualitatively and quantitatively enhanced the museum. And while the collection is still somewhat sparse of major masterpieces by well-known artists, there are hundreds of artistic gems from the brushes of painters most have never heard of.

The founding of a university museum solely confined to “the history and development of religious art from Gothic through the Baroque” and based on the premise that the narrative meaning of works should hold primacy over their brand-name recognition was the conception of Dr. Bob Jones, Jr. (1911–1997). Prior to inheriting leadership of the university, Jones attained considerable success as a Shakespearean actor and theatrical designer, with a deep appreciation for the visual arts. Under his tutelage, the university opened its first two-room gallery in 1951 with approximately forty religious paintings; by 1954, when the first catalogue was published (Bob Jones University Collection of Religious Paintings, Greenville, SC, 1954), the collection had grown to seventy pictures. By 1965, when a new thirty-room museum was inaugurated, holdings had soared to over six hundred European paintings (see Bob Jones University Collection of Religious Paintings, Greenville, SC: Bob Jones University Press, 1962; and Supplement to the Catalogue of the Art Collection, Paintings Acquired 1963–68, Greenville, SC: Bob Jones University Press, 1968), in addition to a smattering of sculpture, period furniture, and a collection of biblical artifacts and Russian icons. Subsequent alterations have pared down the painting collection to some 450 works, most on permanent display in a space whose lush environment of carpeted floors, fabric-covered walls, and piped in music made as much of a stir when the new building first opened as the thematic exclusivity of the collection itself. At that time, Hope described the museum as a “heady” setting that was hardly “conducive to medication” (he surely meant to say “meditation”!), clearly underestimating how complementary this theatrical space is to its predominantly Baroque imagery.

Jones began collecting on a limited budget and at a moment in time when Baroque paintings could be purchased for a relative pittance. With the advice of Carl Hamilton, scholars like the Tietzes and the Suidas, and dealers like Julius Weitzner, Jones was able to amass a significant grouping of works over a relatively short period. The Italian paintings, dating from 1350 to 1750, constitute the largest number of holdings, with Seicento works dominating (D. Stephen Pepper, Bob Jones University Collection of Religious Art: Italian Paintings, Bob Jones University Press: Greenville, SC, 1984). Less numerous are the German, Flemish, Dutch, French, and Spanish paintings, where again the art of the Baroque reigns supreme. Although the emphasis is upon subject matter, works are more conventionally displayed in approximate correspondence with their national origin and in a rough chronological order.

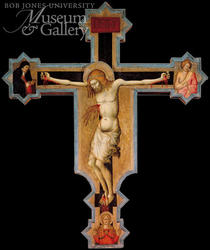

As to be expected, the earliest Italian paintings—attributed to the likes of Tomasso del Mazzo (previously known as the Master of Verdiana), and Florentines Niccolo di Pietro Gerini and Lorenzo de Bicci—consist of golden panels representing standing saints and enthroned Madonnas. Clearly, the standout work here is one of the earliest, a large Crucifix (ca. 1370), given to the little-known Sienese painter Francesco di Vannuccio; its delicate brushwork miraculously evokes a bloody pathos that is exceptionally moving. Bicci di Lorenzo’s still Gothic early fifteenth-century Madonna and Child with St. Anne (in its original gilded frame [ca. 1420–30]), provides an interesting iconographical and stylistic parallel to Masaccio’s early Renaissance Uffizi panel of the same theme. Several intact altarpieces of the early fifteenth century—such as a Madonna and Saints polyptych (late fifteenth century) signed by Pietro Alemanno, and a mammoth-sized and much-abraded Coronation of the Virgin, signed and dated 1470 by the little-known Antonio de Imola—tend to accent lesser artists working in a retardataire manner, and thus convey the weakness of the Quattrocento holdings, particularly its lack of significant Florentine works of an Early Renaissance style. Indeed, the only big-name Florentine picture, from late in the century, is Botticelli’s Madonna and Child with an Angel (ca. 1490–1500), a delicately intimate work whose main figures are unquestionably by the master; it is housed in the polygonal “Tondo Room” together with similarly themed works by minor masters influenced by the lessons of Perugino, Raphael, and Leonardo.

Adjoining galleries are filled with works of the Quattrocento and Cinquecento, again mostly by secondary masters. The most noteworthy of Early Renaissance paintings is the lovely Nativity (late fifteenth century), given to the Master of the Borghese Tondo, while a small Flight into Egypt (ca. 1500) by the Florentine contemporary of Michelangelo, Francesco Granacci, with its exquisitely interwoven sculpted figural forms, well represents the central Italian High Renaissance. Stealing the show, in its cold, calculated composition of convoluted figures adapted from Raphael’s Spasimo di Sicilia (1519), is a Procession to Calvary (1525) by Sodoma, Siena’s sixteenth-century master. Other mannered works are also exceptional, from the exaggerated display of figures in Francesco Cavazzoni’s Finding of the True Cross (ca.1585), to the poised Parmagianesque elegance in Francesco Menzocchi’s Madonna and Child with Saints (ca. 1550), the cultivated artificiality of a brightly colored Ananias Restoring Sight to Saul (ca. 1570)—a theme of unusual iconographical interest—attributed to Vasari’s pupil, Francesco Morandini (called Il Poppo), to the garishly frightful Last Judgment (ca. 1530–50), given to Roman/Neopolitan painter G. F. Criscolo.

Equally satisfying are the sixteenth-century Venetian paintings. Although there are no Titians, a small Bust of Christ (ca. 1545), attributed to Paris Bordone, captures the earlier master’s style and spirit. Both the deliciously poetic Madonna and Child with Saints (ca. 1518) by Vincenzo Catena, set within a colorful landscape with half-length figures, and an elaborate Sacra Conversazione (ca. 1525–30) by Bonifazio Veronese, each display, in its own distinct way, amalgamations from Giovanni Bellini, Giorgione, and Titian. Tintoretto’s large painting, The Queen of Sheba’s Visit to Solomon (ca. 1545–46)—his earliest version of this theme—is a grand display piece set on a perspective stage filled with exotically dressed figures; it is a primary example of Tintoretto’s early development. Palma Giovani’s Birth of the Virgin (ca. 1600–20), compositionally based on Tintoretto, and works by the Bassano family and others complete this pleasant ensemble.

The core of the collection is comprised of several rooms devoted to Italian seventeenth- and eighteenth-century painting; the Baroque holdings were perfectly characterized by the Posners as, “an unconventional, but highly appealing, anthology of the painting of the period” (149). Although some big names—like Caravaggio, the Carraccis, Pietro da Cortona—are absent, the holdings constitute one of the most comprehensive groupings of Italian Baroque paintings in the world, and allow audiences the exceptional opportunity to view images by masters unrepresented or underrepresented outside of Italy. For the most part, the holdings concentrate on lesser-known masters who represent a variety of regional schools, from Bologna and Rome, Naples and Sicily, Florence, Genoa and Venice; together they provide insight into the complexities of the Italian Baroque and a measure of stylistic relationships from place to place and from artist to artist. Presently, these works are displayed over several galleries, although the museum’s curator, John Nolan, has plans to rehang the Italian Baroque works along regional lines.

The Bolognese-based painters are introduced by an altarpiece representing St. Francis of Assisi Receiving the Christ Child from the Virgin, signed and dated in 1607, by Denys Calvaert, the first teacher of Domenichino, Guido Reni, and Albani. Although still emotionally mannered, this work handsomely displays a visionary iconography and the emulation towards saints promoted by the Counter-Reformation. In turn, Domenichino’s refined easel painting of St John the Evangelist (ca. 1625–28) depicts the young saint as a learned author of scripture, rather than an ecstatic visionary. Reni is represented by a series of four bust-length Evangelists (ca. 1630s) somewhat uneven in quality, Matthew and Mark being the better), each inspired as they inscribe their tomes. The Renis are executed in a summary manner, and according to Pepper were rapidly produced and cheaply sold as a means to pay off the artist’s gambling debts. Together with the Domenichino, these paintings denote the varied tendencies of Baroque classicism practiced by some Bolognese adherents of the Carracci following their experiences in Rome. From later Seicento Rome, a dynamically infused classicism is exampled by Carlo Maratta’s Martyrdom of St. Andrew (ca. 1656), derived from a painting by his teacher Andrea Sacchi, while a parallel form of classicism is exemplified in devotional works by Sassoferrato. An early eighteenth-century Holy Family’s Return from Egypt (ca. 1707–15) by Maratta’s pupil, Giuseppe Bartolomeo Chiari, with its soft Cortona-inspired surfaces and blatant sweetness, provides a contrast to the more austere half-length St. James the Greater (ca. 1740–43) by Pompeo Batoni. Originally part of an apostolado executed in the 1740s, this striking canvas follows the conventions of series paintings found in the above-noted works of Domenichino and Reni. Lanfranco’s hand appears in a heavily restored St. Cecilia (ca. 1620–21), while the same musical saint—extremely popular in the seventeenth century—by his Neopolitan follower, Giovanni Battista Beinaschi, better displays the dynamic, painterly qualities inherent in the art of the former. Unfortunately, the art of Guercino has been reduced to a bust-length figure of Jacob Mourning over Joseph’s Coat (ca. 1625) and a bland fragment of an altar representing St. Anthony of Padua (ca. 1658–63); this artist’s impressive Christ on the Mount of Olives (1632)—deemed the collection’s star Bolognese painting by the Posners—has passed to the North Carolina Museum of Art.

Other Italian “schools” are represented by quality works, many by artists not generally known to more than a handful of specialists. From Florence come two meticulously finished devotional works by Carlo Dolci, produced for the court circle of the pious Grand Duchess Victoria of Tuscany, and a beautiful Penitent St. Peter (ca. 1664), perfectly geared to stress the sacrament of confession. Enchanting is a Triumph of David (ca. 1630)—a theme of long-standing popularity in the city—by Dolci’s master, Jacopo Vignalli; here, a richly attired David, holding Goliath’s head and with a large sword on his shoulder, is greeted by music-making females as he gallantly strolls across the foreground while stunted mannequin-like characters also participate in the pageantry. Vignalli’s work points out the peculiarly odd nature of the Florentine Baroque with its mixture of naturalistic details and mannerist elegance. And though the Vignalli deals with a popular theme, one might also mention here the enormous proliferation of Old Testament subjects favored by Italian Baroque masters of all schools, although, unlike the Dutch, these Catholic masters generally continued to interpret such events and personages for their prefigurative or typological qualities.

Practitioners working in Genoa are represented by a potpourri of works, ranging from a beautiful Bolognese-Roman influenced Flight into Egypt (ca. 1615) by Domenico Fiasella; a rare example (Christ in the House of Simon [ca. 1635–45]) from the brushes of Lucca Salterello, a Fiasella pupil; and two (from a series of six) large, anecdotal narratives of the Joseph story—contrasting with Guercino’s solitary figure mentioned above—by Giovanni Battista Carlone. The Venetian school is present with a so-so Bernardo Strozzi and an aggressively overcrowded Expulsion of Hagar (ca. 1630–35) by Francesco Ruschi. The works by Neapolitan-associated masters are truly exceptional, from the magnificent Mateo Preti Christ Setting the Child in the Midst of the Disciples (ca. 1680–85), a rare and forceful interpretation of the passage from Matthew, to Luca Giordano’s large, action-packed Christ Driving the Merchants from the Temple (ca. 1660), a superb example of his early maniera dorato produced soon after his experience of Veronese in Venice in the 1650s. Pacecco de Rosa’s Martyrdom of St. Lawrence (ca. 1635–40), in turn, relieves this popular subject of much of its potential horror by tempering its Ribera-inspired realism with a dose of classicism, visible in the idealization of the young, naked saint stretched across the foreground. The collection also includes a calm Salvator Rosa Landscape with the Baptism of Christ (ca. 1655–60) from his Florentine period, and an imposing canvas—with both Caravaggesque and Riberesque influences—by the Sicilian-based Pietro Novelli (called Il Monrealese). This picture’s unusual iconography presents Gabriel summoned by the Trinity in the heavens before being dispatched to announce the Incarnation to Mary, a tiny figure lost in the lower left. As rare as the iconography, so is the very presence of a work by this accomplished master in a U.S. collection. And much the same is true for many of these lesser-known yet spectacularly diverse Italian Baroque masters.

The impact of the art of Caravaggio is ever present, on Italian art and otherwise. Among the Italians there is a purported version of Orazio Gentileschi’s Appearance of the Angel to Martyrs Cecilia, Valeriano and Tiburzio (ca. 1620—21) the autograph original is in the Brera, Milan); The Body of Christ Prepared for Burial (signed and dated 1616) by Merisi’s nemesis, Giovanni Baglione, which, while compositionally drawn from Caravaggio’s Deposition of 1603 and retaining his model’s sharp lighting, is essentially tame and idealized in nature; and a Christ Disputing with the Elders (ca.1628–29), presently attributed to Sienese artist Rutilio Manetti, executed in the Manfredi-manner. Most interesting are the several works of Dutch, French, and Flemish artists affected by the art of Caravaggio. Excellent examples from the hands of Catholic, Utrecht-based Caravaggisti are present, including a nocturnal Holy Family in the Carpenter’s Shop (ca. 1617–20) by Gerrit van Honthorst, featuring Joseph as the main protagonist, and Jan van Bijlert’s iconographically interesting rendition of Mary Magdalen Turning from the World to Christ (late 1620s). Other Dutch works are attributed to Hendrick Ter Brugghen and Pieter Fransz. de Grebber, the latter represented by a Caravaggesque Adoration of the Shepherds (ca. 1625–30) presented as a wholesome Dutch equivalent to a Norman Rockwell, while Matthias Stomer’s early Flight of Lot from Sodom (before 1630) is indebted to both the Utrecht Caravaggisti and Rubens. In addition, there is an outstanding collection of Rembrandt-related masters, including Govaert Flinck, Gerbrand van den Eeckhout, Jan Victors, Constantijn Adrian van Renesse, and Willem de Poorter. Their images are mostly of Old Testament personages—Solomon, Joseph, and Esther stand out—and account for the relatively few images in the collection that bear witness, in their choice and interpretation of subject matter, to the effects of the Protestant Reformation.

Among the limited Flemish Baroque holdings is Rubens’s Crucified Christ (ca.1610), identified as a studio “prototype”; an attractive Van Dyck Madonna of Sorrows (ca. 1625–30); and a stunningly magnificent Adoration of the Magi (1652) by Jan Boeckhorst, a rare mature work that displays the influence of Rubens, Jordaens, and Van Dyck. The small but encompassing French paintings are dominated by Philippe de Champaigne’s severe, pathos-driven Man of Sorrow (ca.1655), which replicates a version painted by the master for the Jansenist church at Port Royal. The impact of Caravaggio and the Utrecht Caravaggisti is again evident in both the style and subject matter of Trophile Bigot’s St. Sebastian Tended by St. Irene (1620s) and Jacques Stella’s nocturnally Correggesque Adoration of the Shepherds (ca. 1650–57), both of which contrast with the sparkling luminosity of Claude Vignon paintings and the classicism in those of Charles Le Brun and his student Jean Baptiste Jouvenet. A reasonable facsimile of Poussin’s classical landscapes is provided by the Hiding of Moses (ca. 1650) by Sébastian Bourdon.

Like the French, Spanish holdings are surprisingly good, although aside from Jusepe Ribera’s moving Christ of Derision (1638), works by two other seventeenth-century Spanish greats are disappointing. Zurbarán’s Annunciation (ca. 1638–40) is a weak takeoff on his masterpiece at Grenoble, while the so-called Murillo Good Shepherd (ca. 1665–70) is worn and fatuous. Nevertheless, the collection offers a glimpse of little-known Spanish Baroque masters from the austerely realistic early century, represented by an extraordinarily raw, monumental Scene from the Life of St. Catherine (ca. 1628–29) by Francisco Herrera the Elder, to the colorful, painterly works of later Flemish and Italian-influenced masters like José Antolínez’s Michael Vanquishing Satan (ca. 1660–75). This work may be constructively compared to an Italian version of the theme in the Bob Jones collection by Giovanni Andrea Sirani that copies Reni’s famous rendition, an engraving of which was also the source for Antolínez’s painting. Moving back in time, there is a hodgepodge of medieval and “Renaissance” panels, among the latter a predella series by the Master of Riofrio (whose kings and prophets reflect upon the work of Pedro Berruguete), a panel by Juan de Flandes, and an excellent Juan de Juanes Pentecost (ca.1565–75).

As Jones’s initial predilections tended toward Netherlandish art, early on he collected a large number of panels, many with debatable attributions and some of lesser quality; they are displayed in the final three Gothic “period” rooms of the museum. Among a specious Roger van der Weyden and panels more credibly attributed to Gerard David and Albrecht Bouts, Colijn de Coter’s St. Michael Weighing Souls and St. Agnes (ca. 1490–1500), originally wings of a triptych now connected as one, stands out for its intricate detail and its iconographical complexities; the scale held by Michael, and tugged upon by a devil, is weighed down by a wax seal imprinted with an image of Christ in Glory. Interesting as well is the charming Madonna of the Fireplace (ca. 1500), attributed to a young Jan Goessart, depicting Mary seated beside a fireplace warming her hands and the baby Jesus’ bottom; a basket of diapers and the Child’s stroller rest on the tiled floor. Far more expressive is the Passion scene, Way to Calvary (early sixteenth century), the signature piece of the so-called Master of the Holy Blood, which is displayed alongside Lucas Cranach’s explicitly Protestant Allegory on the Fall and Redemption of Man (ca. 1530); the Elder is likewise represented by a spare, violent image of the rarely illustrated Joab Slaying Abner (ca. 1530–40). There are also an abundant number of Italianized “Renaissance” works by Flemish, Dutch, and German masters, including an intricately detailed triptych by Jan Swart van Groningen in a style reflecting the Antwerp mannerists. The best of the Romanist paintings are those attributed to Jan van Scorel (Christ and the Samaritan Woman [ca. 1525–30]) and his pupil Martin van Heemskerck (Jonas under the Gourd Vine at Ninevah [ca. 1555–65]), while a refreshingly wonderful Holy Family (1565) monogrammed by Jacob Beuckelaer offers a taste of down-home religious sentiment in a genre-like ambiance. As a whole, the Northern fifteenth- and sixteenth-century collection is a bit uneven, though it should not be underestimated.

Finally, one must make quick note of a handful of post-baroque paintings, most of which are anti-climatic to the great religious imagery noted above. Certainly Gustave Doré’s paintings, particularly Christ Taking up the Cross (1883), are flamboyantly engaging, but of greater acclaim are seven of twelve surviving paintings from the Revealed Religion series (1781–1801) by Benjamin West. Commissioned by the ill-fated English King George III from his court painter, and originally intended for a chapel in Windsor Castle, they are today housed in the War Memorial Chapel on the Bob Jones campus.

Over the years, the Bob Jones Museum has generously lent its paintings to national and international shows, including two U.S. traveling exhibitions that displayed a large sampling of works (Baroque Paintings from the Bob Jones University Collection, 1984; Botticelli to Tiepolo: Three Centuries of Italian Painting from Bob Jones University, 1994–95). However, it is only through an on-site visit to Greenville that one can fully comprehend the exceptional quality and range of the Bob Jones holdings, and truly understand the spirit in which the university collection was created and is maintained.

The Bob Jones University Museum and Gallery collection can be visited online at www.bjumg.org.

David M. Kowal

Professor, Department of Art History, School of the Arts, College of Charleston