- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

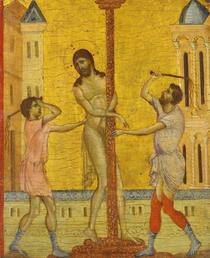

Over the last few years, our knowledge of Tuscan painting in the late duecento has expanded considerably. In Siena, the recent unveiling of frescoes in the crypt of the cathedral has challenged our assumptions about late medieval Italian art. Previously unknown panel paintings have come to light as well, among them a dazzling small panel of the Enthroned Virgin and Child, recently acquired from a private collection by the National Gallery in London, and attributed to Cimabue by the National Gallery’s curator of early Italian art, Dillian Gordon. Gordon went on to associate the new acquisition with the closely related Flagellation in the Frick Collection—its authorship the subject of much debate by an earlier generation of scholars, and still uncertain until that point. She not only argued convincingly that the two panels were by the same hand, but suggested that the two were once part of the same ensemble (Apollo 157 (2003), 32–36).

The two panels were exhibited together, first (March–June, 2005) at the Museo di San Matteo in Pisa, then in London at the National Gallery (October 2005–January 2006); it was only this fall that they were displayed together in the United States. Holly Flora, then an Andrew W. Mellon Curatorial Fellow at the Frick and now curator at the Museum of Biblical Art in New York, organized the small exhibition that united—or reunited—the two. In addition to the two Cimabue panels, the exhibition included thoughtfully chosen works from New York public collections: two Florentine panel paintings from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (a small triptych by the Magdalen Master, probably from the third quarter of the duecento, and a similarly scaled diptych by Pacino di Bonaguida from the early trecento), four folios from a manuscript by Pacino in the Morgan Library, and an Umbrian reliquary diptych also from the Met. Though the exhibition has now closed, a well-illustrated catalogue provides some sense of its aims and scope. The catalogue includes Rachel Billinge’s succinct discussion of the relevant technical matters and a longer essay by Flora that offers a salient account of all the relevant aspects of the exhibition: a history of the Frick panel, an overview of Cimabue’s oeuvre, a discussion of Helen Clay Frick’s patronage of early Italian painting, an account of the discovery of the National Gallery panel, a consideration of the original context of the two panels, a discussion of Franciscan devotional thought and practice, and a more focused exploration of the two panels’ iconographic and devotional contexts.

Visitors to the exhibition might protest the conditions imposed on the show—the close quarters of the Frick’s Cabinet Gallery where it was installed, and the restriction of comparative works to those from New York public collections. But this is an ungenerous response: this exhibition afforded viewers in the United States the opportunity to compare these two works at close hand, and that opportunity is not likely to occur again soon. The two panels are unquestionably related. Flora calls attention to the red borders that surround each panel, though the borders have been cropped out of the photographs in the catalogue. Such borders are not uncommon in late duecento and early trecento works that combine several narratives in a single panel—as Flora observes, similar red borders divide the scenes in the diptych by Pacino included in the exhibition (25)—but the detail is worth noting. Stylistic and compositional echoes also link the two small panels: the delicate pinks and mauves worn by the angels flanking the Virgin’s throne find their counterparts in the tunics of the men scourging Christ; the interplay of the gestures of mother and child is paradoxically echoed in the juxtaposing of Christ’s crossed hands and the hand of his scourger; the diaphanous cloth on which the Virgin sits anticipates the virtual transparency of Christ’s loincloth in the Flagellation.

Other links between the two panels include their nearly identical dimensions and technical matters such as the craquelure. But despite these connections, questions remain. One of the most vexing, as Annemarie Weyl Carr observed, is the scale of the figures, which corresponds closely in the two panels. It is very difficult to point to an example of duecento or early trecento panel painting in which the Virgin appears in the same scale as figures from a narrative cycle in the same ensemble. In the catalogue, Flora alludes to this problem, noting that “the Virgin and Child Enthroned and the Flagellation were almost never rendered in the same scale in the same work” (25). Following Gordon, Flora adduces the reconstruction of a diptych attributed to the Master of San Martino alla Palma, in which eight equally sized panels—the enthroned Virgin and Child, and seven narrative scenes from the life of Christ—were likely joined together. But even here, the scale of the figures differs considerably, with the enthroned Virgin far larger than the figures in the narratives. The same privileging of the Virgin is clear in the diptych by Pacino included in the exhibition. What, then, are we to make of these discrepancies? Billinge’s essay on her technical examination of the two Cimabue panels may sound a note of caution: she refers to them as “presumably part of the same work” (40). Perhaps we might recall the minuscule rate of survival for duecento paintings—E. B. Garrison’s estimate of one percent is not implausible—and consider the possibility that Cimabue and his shop produced dozens of small devotional panels like these; if we assume that Cimabue (ca. 1240–1302) worked for over forty years, as seems likely, the number of such panels that originally existed could easily be higher still. Whether or not the National Gallery Virgin and Child and the Frick Flagellation once were part of the same ensemble, however, the organizers of this exhibition deserve our gratitude for bringing these two important panels and the related works together, so that viewers might consider them in tandem and ponder the questions they raise.

Anne Derbes

Professor, Department of Art and Archaeology, Hood College