- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Comprised of one wonderful work after another, Villa America: American Modern, 1900–1950 makes a strong impression. Beyond presenting many excellent works, the exhibition illuminates the visual dialogue concerning style and theme undertaken between and among U.S. artists during the first half of the twentieth century, a particularly exciting period in U.S. art history. With its illuminating juxtapositions of works and its many self-portraits, Villa America brings to life the excitement and energy that percolated within the U.S. art world during this now rather distant era. The exhibition presents for the first time selections from the private collection of Myron Kunin, the former owner of Regis Corporation. Organized by the Orange County Museum and curated by Elizabeth Armstrong, the exhibition originated at the Orange County Museum in Newport Beach, followed by a run at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts—Minneapolis is Kunin’s home—and closes at the Marion Koogler McNay Art Museum in San Antonio.

As one would expect, the exhibition opens with an exploration of European modernism’s influence on the many young, impressionable U.S. artists who traveled mainly to Paris and Berlin during the first few decades of the twentieth century. We see Stuart Davis, Morgan Russell, Alfred Mauer, Morton Schamberg, and many others experimenting with the abstract styles they discovered abroad. Abstract Tree Forms, a small 1914 oil painting by Charles Sheeler, oozes with enthusiasm for the new with its flat, brightly colored planes pieced together into an abstract landscape. Max Weber’s Two Seated Figures of 1910 similarly suggests the exhilaration of discovery. Inscribed with confident, direct brushstrokes on a large sheet of cardboard just a few years after Pablo Picasso’s outrageous Les Demoiselles D’Avignon, Weber’s two blocky nudes bubble with a sensuality that attests not only to the allure of the female form, but equally to the powerful attraction the artist felt for the visual language of the European avant-garde.

Pushing beyond simply demonstrating influences from abroad, one of Villa America‘s strengths is that it sets up conversations between works that suggest not direct influences in style, but rather a community of artists exploring a set of aesthetic ideas. These distant yet pertinent correspondences of forms and ideas are often lost in more typical monographic treatments of individual artists. For example, the angular planes of Weber’s Two Seated Figures resonate with the crystalline forms of Naum Gabo’s 1916 sculpted Constructed Head No. 2, which at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts exhibition installation rests on a pedestal beside it. Gabo’s reductive, hard-edged construction in turn links visually with the flat planes of Marsden Hartley’s 1915 still life, A Nice Time, hung on an adjacent wall. Visual connections like these are choreographed throughout the exhibition. Paintings by Arthur Dove, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Hartley—artists who in fact worked in close proximity to one another—are grouped together, demonstrating similarities in aesthetic sensibility. In short, the arrangement of works in Villa America provides a kind of visual chorus of color and shape that effectively communicates an atmosphere of dynamic and heady exchange of ideas.

In some cases the viewer can follow the stylistic development of an individual artist in a selection of pieces spanning decades, hung throughout the exhibition. For example, a public familiar with Davis’s energetic hard-edged abstractions of the 1930s will be enchanted by the examples of his early work on view in Villa America. The zigzagging shapes of darkening sea, waterlogged beach, and cloud-streaked sky featured in Ebb Tide, Provincetown of 1913 represent the germs of what would in time become Davis’s mature style. But there is more. Davis’s Self-Portrait of 1913 illustrates a moody naturalist style, while the memorable Portrait of a Man from 1914 is a bright, graphic painting reminiscent of Van Gogh. Of course, Davis’s exploration of analytic cubism can be seen in the near monochromatic still-life studies of the late twenties and early thirties. The viewer gets the sense of Davis here as an artist working within a vital community, intelligently and creatively responding to a plethora of aesthetic stimuli. We see this breadth of artistic vision and growth in other artists featured in the exhibition as well, particularly in the selection of paintings by Hartley, whose style underwent significant change from the period of the still-life abstractions of the teens, the rugged landscapes of the 1930s, to the social realist subjects of the 1940s—all of which are represented in Villa America.

Kunin amassed a remarkable collection of self-portraits, many of which are grouped together at the heart of Villa America. These serve a humanizing function within the exhibition, balancing out, as it were, the highly theoretical concerns of so much of the work on view in the exhibition. For example, the sober, realist Self-Portrait of 1911 by Schamberg makes a dramatic contrast to the artist’s radically abstract Figure A (Geometrical Patterns) of 1913, also on view in the show. John Steuart Curry, with paintbrushes in hand and puffing on a pipe, takes a break from his work to amiably acknowledge the viewer in his 1935 Self-Portrait. By contrast, in his Self-Portrait of the same year Grant Wood stares accusingly outward at the viewer; images of the nameless masses stand behind the artist, icons of his evident concern. George Tooker’s Self-Portrait of 1947, a hypnotic study in platonic form, is one of the most striking pieces on view. Recalling Piero della Robia’s roundels of the Renaissance period and organized around the circular shape of the nautilus shell held by the artist in the painting, Tooker’s work features piercing blue eyes staring forward from a perfectly, though unnaturally, rounded head. The self-portraits together with the grouping of studio nudes near by—sensuous canvases featuring fleshy female bodies by Robert Henri, Arthur B. Carles, George Luks, and Edwin Dickinson, among others—offer the viewer palpable images of real people working in real spaces.

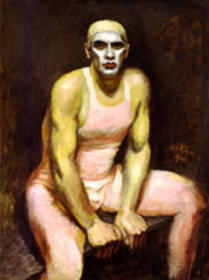

The exhibition’s final gallery focuses on the theme of spectacle. Reginald Marsh’s Star Burlesque of 1933 announces this with its sexy, nearly naked female performer. Marsh aligns the viewer’s vantage point on the stage with this blond bombshell, who looks out at the licentious faces of the all-male audience seated in a garish Baroque theater. Nearby we see circus performers, like Eli Nadelman’s diminutive sculptured Acrobat of 1916 performing a summersault and Walt Kuhn’s 1946 Roberto, a beefy male circus performer wearing a pale pink leotard and an enigmatic and melancholy facial expression. Spectacle also includes the action on the street. African American folk musicians pose in snappy outfits before a red brick wall in Romare Bearden’s powerful Folk Musicians of 1941–42, and a lost soul kneels on the street in distraught prayer in Hartley’s poignant 1942 Prayer on Park Avenue. Most spectacularly is Paul Cadmus’s Main Street of 1937, a large canvas picturing a tangle of colorful characters playing out a less-than-heroic narrative of life as it unfolds on the main drag of a small town in the United States. A pretty, young tennis player and a leggy brunette in short shorts cause a stir as they pass a group of men loitering in front of a drugstore. The disorder, sexuality, and celebration of leisure that characterize Cadmus’s painting caused it to be rejected by the post office it was originally commissioned to decorate.

Aside from offering a rich and rewarding overview of trends and themes that preoccupied U.S. artists during the first half of the twentieth century, Villa America also represents Kunin’s vision of the period; he is in a sense the real center of the exhibition. One cannot see the exhibition without thinking about the commitment and passion that drove this collector. Unhampered by museum committees and other institutional constraints that shape the choices of professional curators, Kunin sought out and purchased all of the fine works on view. Villa America attests to Kunin’s eye for quality, but the many self-portraits he collected and his exploration of the long careers of individual artists perhaps also speak of his desire to know these artists and to reanimate the voices of their time.

Patricia Briggs

Assistant Professor, Liberal Arts, Minneapolis College of Art and Design