- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

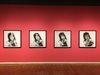

A row of framed black-and-white photographs of artist Judy Baca hang on a hot-pink wall. Titled Judith F. Baca as La Pachuca (1976), this series depicts Baca styled as a “Pachuca,” a Mexican American female stereotype from the 1950s. In the photos, Baca wears a white, collared, button-up top, with a pack of Marlboros tucked into the cuff of her rolled-up sleeve. Her dark hair is teased, her painted eyebrows are dramatically arched, her eyeliner winged, her lips outlined, and a scarf is knotted around her neck. In each photograph, she puffs on a cigarette poised between long-nailed fingers, with clouds of smoke obscuring her face. Performing the role of the Pachuca, the female counterpart of the Pachuco, often associated with zoot suits and delinquency, Baca presents an image of Chicana womanhood that symbolically threatens both midcentury white middle-class femininity and the Catholic ideals of Mexican American womanhood.

This series is just one of many early works by Baca that appeared in her first major museum retrospective, Judy Baca: Memorias de Nuestra Tierra, at the Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA) in Long Beach, California. Organized by MOLAA Chief Curator Gabriela Urtiaga and guest curator Alessandra Moctezuma, the exhibition examines the career—extending more than forty years—of the seventy-five-year-old Chicana muralist, artist, scholar, and activist, including her better-known public art projects and her lesser-known small-scale and personal works. The exhibition was split between several galleries organized around different themes. The Pachuca photographs appeared in the first gallery, titled “Womanist Gallery: Female Power Represented,” which contained Baca’s early works, including journals, drawings, and paintings from the early 1970s, and designs and mock-ups for her murals, including preparatory drawings for her 1984 Olympics mural commemorating female marathon runners. In addition to the pink wall with the Pachuca photographs, the room’s other walls were all painted in bright colors, including a sunny yellow and a dark blue.

Positioned in the middle of the room near the Pachuca photographs stood a sculptural object titled Las Tres Forever (2021), a re-creation of the 1976 installation and performance Las Tres Marias (The Three Marias), in which Baca performed the Pachuca persona at the feminist Woman’s Building in Los Angeles. Las Tres Forever takes the form of a hinged, three-paneled screen, with a different figure appearing on each panel. The left-hand panel depicts a life-size, full-body drawn portrait of Baca-as-Pachuca in black, white, and red. She wears a tight black pencil skirt cinched at the waist with a shiny red belt, and red Mary Janes on her feet. Her face and hair are the same as in the Pachuca photographs, but now her earrings and neck scarf stand out as red accents. A similarly drawn companion figure also appears on the right-hand panel. This full-length portrait depicts a real woman named Flaquita, who at the time was a Chola, a female member of a Mexican American gang. The figure stands facing the viewer, wearing a black V-neck sweater and baggy pants, her hands digging casually into her pockets. Her long, dark hair frames her minimally made-up face and mute expression as she gazes out ambivalently at the viewer.

In contrast to the two wings, the central panel is a mirror that reflects the image of any viewer who stands before it. Thus, the reflection of one’s own body becomes sandwiched between the images of the Pachuca and the Chola, each representing the past and present of Mexican American women’s “bad girl” subcultures. The work’s earlier title, Las Tres Marias, invokes the three Marys of the Crucifixion story. As such, Baca replaces the traditional humble and passive image of the Virgin Mary with representations of fierce Chicana women—one femme and the other butch, both strong and self-possessed—as a commentary on the limited range of Mexican American female types in both eras. Depending on whose reflection occupies the mirrored panel at center, Baca also seems to indict our own complicity as viewers in buying into these limiting and socially constructed identities.

Another main gallery space was dedicated to a virtual reproduction of Baca’s most iconic work, The Great Wall of Los Angeles (1974–79), an epic, half-mile-long mural located along the Tujunga Wash in the San Fernando Valley that represents the history of California from prehistory to the mid-twentieth century. The mural was conceived by Baca and executed through the Social and Public Art Resource Center (SPARC; an arts and activism organization she founded in 1976), with over 400 local youths and community members working alongside artists, oral historians, ethnologists, and scholars. Since the mural is best viewed in situ, re-creating it within the context of a museum exhibition proved to be a challenge. The curators’ partly successful solution was to attempt to capture the mural as a scrolling video projected on all four walls of the gallery set to music, as an immersive audiovisual experience.

A third gallery space, titled “Public Art Survey: From Painted Murals to Digital Works,” introduced visitors to a range of projects Baca spearheaded with SPARC. The room’s bright yellow and teal walls housed a number of the artist’s brightly painted sculptures of seated Pancho-figures on multicolored Mexican serape blankets, as well as mural preparatory drawings and maquettes for some of her better-known commissions, including her traveling mural project World Wall: A Vision of the Future Without Fear (1986–present); the Guadalupe Mural Project (City Hall, Guadalupe, CA, 1990); the César Chavez Monument (San Jose State University, 2008); La Memoria de Nuestra Tierra: Colorado (Denver International Airport, 2000); and the earlier version of the latter mural, La Memoria de Nuestra Tierra, California (1996), an acrylic-on-canvas mural located at the University of Southern California (USC).

Commissioned in 1996, La Memoria de Nuestra Tierra, California honors the titular theme of the memory of the land by depicting a Southern California landscape with a river snaking through verdant hills and farmland on the left and a dry, orange mountain range on the right. In the center the river transforms into a freeway, which at the bottom opens onto a brick Kiva framed by agave leaves. To the right, an earth goddess emerges out of the orange hills, from a supine to an upright position, while below her throngs of protesters pour into the streets, mimicking the curving path of the central river. Included in this exhibition were two preparatory drawings for the work, one beautifully rendered in colored pencil and another in graphite labeled at the bottom in Baca’s neat handwriting, “USC Mural Commission in Progress, with USC president’s comments and administrators’ comments.”

It was this latter drawing that proved to be the most compelling work in the entire exhibition for its inclusion of handwritten annotations on all four of the image’s margins that outline the disturbing feedback Baca received when she presented the mural proposal to the university’s administration. For instance, an image of a Native American is accompanied by a blue text (representing the administration’s words) asking, “Why are there Indians in a Mexican Work?” Baca provides her own response to this uninformed question directly below: “Do you really not know?” Other blue comments surround the image of the earth goddess: “What is she doing?” “Why is she so angry?” “Couldn’t the sleeping giant be happier?” Additional ignorant comments dot the edges, with the overall summation from the administrators appearing at the top: “Generally, Judy, we believe that this mural is not understandable to an Anglo audience and is too negative. The history you represent is depressing.” Baca’s acerbic response appears below: “I was invited to make a Chicano/Latino themed mural and I want to work with Latino students to conceptualize the imagery. I have done that. Besides I did not make the history, I just paint about it.” Baca’s ability to “talk back” to administrators through her notes sheds light on the institutional obstacles she has faced as a Chicana muralist throughout her career, as well as the shocking lack of historical knowledge about Mexican American and Indigenous histories in Southern California among those in positions of power.

I wish the exhibition had included more moments like this one and less works in other media. The show was at its best when it focused on the preparatory drawings and maquettes for Baca’s murals, which reveal the many stages of preplanning and negotiation necessary to execute them. Baca’s more recent digital collage murals, which are given too much space in the exhibition, are less dynamic and engaging than the folkloric stylings of her earlier, hand-painted murals. The curatorial impulse to paint the gallery walls—likely intended to evoke the bright colors of Mexican architecture—was unnecessary with such brightly colored works, and in the end, did more to distract from rather than complement them. The galleries were also too packed, resulting in what felt like an unedited exhibition. A tighter selection of works, with more space dedicated to each one, would have yielded a more focused and coherent show. Despite these drawbacks, this presentation was a necessary and comprehensive consideration of the legacy of an overlooked Southern California woman artist, and an important corrective to art histories that have ignored her significant contributions to US public art.

Gillian Sneed

School of Art + Design, San Diego State University