- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

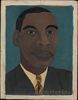

Conceptions of race have limited the trajectory of American art history since its inception in the early nineteenth century. Anne Monahan reckons with this condition in Horace Pippin, American Modern, building her arguments alongside a systematic dismantling of the scaffolding of racist ideology that has supported many misunderstandings of the painter Horace Pippin (1888–1946). Her groundbreaking book helps to deracinate a powerful “art-historical caste system” that has consistently mistreated autodidacts, particularly those of color (2). Horace Pippin shines in the midst of an overdue racial reckoning in the United States, to which it makes a substantial scholarly contribution.

Pivotal to the success of Monahan’s project is her exploration of how “racecraft” (as termed by historian Barbara Fields and her sister, sociologist Karen Fields), “the process whereby racist ideas become codified as supposedly neutral facts via repetition and publication,” has conditioned responses to Pippin’s work (18, emphasis in original). Monahan recoups the racially charged dynamics affecting Pippin’s career, while reconstituting his agency in its formulation. A landmark contribution to American modernism, Monahan’s book repositions Pippin within the field as it scrutinizes the facture of the field itself. Her chapters—“Autobiography,” “Labor,” “Process,” “Gifts”—fortify each other through overlapping arguments in a volume that is riveting at every turn.

Borrowing investigative tools from literary theory, “Autobiography” rejects the predominant role of Pippin’s writings in earlier scholarship. Instead, Monahan’s analyses reveal Pippin’s tendency to conflate personal history with imaginative substitutions. The Ending of the War, Starting Home (1930–33), for instance, draws in some ways from Pippin’s combat experience during World War I, yet not as a facsimile of an event, as has been previously assumed. Analyzing his writings against and alongside a selection of his visual production, Monahan demonstrates the conceptual cracks between them, in the process revealing Pippin’s “willingness to exploit [autobiographical] indeterminacy” (69). Given his unpredictability as a narrator, whose story features many ambiguities and contradictions, Monahan reorients attention toward Pippin’s art through careful consideration of nearly half of the 140 works he created between the mid-1920s and his death in 1946. Her arguments hinge on deep, formal interrogation of his art as the primary material. That she never endeavors to pin Pippin down is part of the success of her scholarship (and part of what differentiates it from other recent work on Pippin), a form of art historical analysis that asks as many questions as provides answers, constantly probing how best to assess the significance of “arguably the most visible black artist of his day” (74).

Uniting Pippin’s labor as an artist on assignment with the various forms of work he images, “Labor” evidences Pippin’s repeated flexes of creative license that shaped a resourceful artistic practice and asserted his legitimacy as an artist. In this nuanced account of his rise to prominence, Monahan argues that Pippin voiced critical anti-racist sentiment in his paintings of cotton farms. In Old Black Joe (1943), which Pippin painted for one of the two major commissions he received in the 1940s, a seated, elderly Black man in the foreground of a plantation scene wears a concerned expression, looking head-on at the painting’s imagined viewers while twisting to his left toward a small white girl. She is tethered to his cane, and he is working as her babysitter, thus tending to a child who will one day “surveil and control him as he does her here” (94). A large, seeping black shadow encompasses Joe, a visual manifestation, Monahan argues, of his agony and its command over him under the restrictions of systemic inequality.

While a pronounced dark shadow with no obvious correlation seems a blatant symbol of Joe’s diffusive unease, Monahan elegantly demonstrates that the culture wars of the 1940s commercial mainstream defused Pippin’s condemnation of racial injustice through commodification. His white viewers misunderstood his work as nostalgia for a bygone, pre–Civil War era and so they missed his critiques. That such misunderstanding advanced Pippin’s career as a painter of sentimental plantation imagery indicates the intricacies of coming to terms with Pippin’s professional circumstances, in which he weighed the “privilege and opportunity” that garnered important commissions with the “broader ethical and moral imperatives” to offer a condemnatory message (73).

“Process” substantiates Pippin’s working method as more complex than previously recorded, and in the process refutes Pippin’s “primitivism” and discovery by others. Monahan reveals Pippin’s knowledge of art history, consideration of the work of his peers and forerunners, use of assorted period sources, and inclination to rework and revise his art based on his work’s reception. All of this calculation runs counter to Pippin’s claims that “the pictures which I have already painted comes [sic] to me in my mind, and if to me it is a worth while picture. I paint it [sic]” (210). As an artist whose achievements were often credited to other people—to his dealer and agent Robert Carlen, collector Albert Barnes, and curator Christian Brinton, among others—it is no wonder he would have been “cagey about his influences,” as Monahan reveals, even “pretending to invent subjects” (138). We can understand the protective impulse to safeguard one’s own creative agency when it was so consistently anticipated and placed elsewhere. Monahan validates the complexity of Pippin’s creative practice, including his willingness to pretend to his audience that he was the homespun artist they expected to find, in what appears to be his own investment in entrepreneurial gain.

Still, as Monahan’s examination of Pippin’s series of paintings on both Abraham Lincoln and John Brown show, Pippin took drastic liberties with print sources to create personalized versions of historical events that matched his critical purview. In John Brown Going to His Hanging (1942), he inserted a mob of men into the lower right-hand corner of his reconstruction, the most prominent of whom holds a noose, perhaps meaning to highlight the “scourge of lynching in the United States” (151). Next to them, Pippin inserted the figure of a Black woman wearing a shawl whose bright blue dress and expression of disgust command attention. Monahan convincingly argues that Pippin meant for her to be recognized by discerning viewers as Sojourner Truth, noting that her placement near Pippin’s signature, as well as the matching of his signature’s color to her shawl, announced his affinity for her. I would develop this equivalence even further, prompted by Monahan’s analysis, adding that Truth chose to print a slogan on the front of her cartes de visite—“I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance”—that announced her ownership of the images and command over their dissemination. Truth sold her cards to market and support abolitionist causes. Pippin’s likely inclusion of her in this racially charged work proclaims his similar deliberate deployment of imagery to advance his career.

Like an art historical private eye working on a series of cases, Monahan tracks the provenances and physical lives of Pippin’s paintings in chapter 4, informed predominantly by Pierre Bourdieu’s gift theory. She relocates attention away from the significant work of his dealer and curators toward his own acts of generosity—gifting paintings to socially influential individuals, for example—that inadvertently or not cultivated a successful career. In the process of tracing Pippin’s gifting history, Monahan recoups the overlooked citizenries that helped to promote Pippin, such as the Black community of West Chester, Pennsylvania. For instance, while the details of his acquisition are unknown, a local barber was the original owner of The Buffalo Hunt (1933). He endorsed Pippin’s career by hanging the painting in his place of business, then loaned it to two important exhibitions and finally sold it, via Carlen, to the Whitney Museum of American Art. Even now, the records for Buffalo Hunt remain “whitewashed,” commencing with the Whitney purchase (163).

Only after untangling the threads of racecraft that have persistently clouded considerations of Pippin does Monahan more fully explore his formal refinement and his kinship to the modernist avant-garde. By analyzing his underexamined still lifes, a body of work that composes nearly one fifth of his oeuvre, she demonstrates his dialogue with contemporary art. The narrative arc of Monahan’s skillfully shaped book leads us, in the end, to appreciate Ad Reinhardt’s placement of Pippin as the singular bird in flight above his tree of modern art, a rendering of Pippin that fittingly “frames his distance as agency, not exile” (206).

Meticulously researched and refreshingly reliant on diverse existing sources (a climatologist, for instance, and an expert on heirloom beans), Horace Pippin, American Modern establishes Pippin as an active maker of his career. At the same time, it centralizes uncertainties and questions to probe a more expansive study of Pippin’s work, seeing him “and his project in his time with fresh eyes” (19). Throughout, Monahan’s conjectures are riveting yet often openly hypothetical. This willingness to speculate in a language of potential indexes a rich series of possibilities for Pippin’s practice. Offering correctives to the record, including her own, time and again Monahan investigates avenues for further research on Pippin. She models a form of scholarship that asks questions to which there are no current answers, stewarding future work with an authority she amply earns.

Clara Barnhart

Lecturer, Department of Art, Smith College