- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

When the artist Jack Whitten (b. 1939) refers to his studio as a laboratory, he is speaking literally, not metaphorically. Fridges and industrial freezers are stocked with muffin tins, pans, and molds of all kinds filled with acrylic paint. Covering the walls are tools of every shape and size—many of which are homemade concoctions. Whitten even looks the part of a scientist; his studio uniform consists of a paint-splattered white lab coat and sneakers he spray-painted silver. Although Whitten frequently acknowledges his debt to Abstract Expressionist painters such as Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Barnett Newman, and Norman Lewis—artists he befriended after moving to New York from the South in 1960—he credits his decision to be an artist to an individual he never met: George Washington Carver (1860–1943). As an undergraduate at Tuskegee Institute, the famed African American university in Alabama (Booker T. Washington was the school’s first president), Whitten supported his pre-med ambitions by working part time in janitorial services at a museum dedicated to Carver. Born into slavery, Carver became a world-renowned inventor, researcher, and educator. In 1941, Time magazine called him a “Black Leonardo.” This formative experience as a janitor at the Carver Museum led Whitten to abandon his medical aspirations and pursue a career as an artist, but Carver’s life also demonstrated to Whitten that he could bring the spirit of scientific investigation to his practice as a painter. In a 1994 interview for BOMB magazine, Whitten stated: “I’m convinced today that a lot of my attitudes toward painting and making, and experimentation came from George Washington Carver. He made his own pigments, his own paints, from his inventions with peanuts. The obsession with invention and discovery impressed me.”

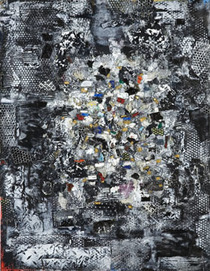

The exhibition Jack Whitten: Five Decades of Painting, curated by Kathryn Kanjo at the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego (MCASD), attests to Whitten’s place as one of the great experimental abstract painters of our day. So diverse is his output that visitors to the show unfamiliar with Whitten’s art may wonder whether the exhibition is a group show. Animated gestural abstractions painted in a hot palette from the 1960s give way to a gallery of coolly elegant “slab” paintings from the 1970s, each featuring a predominant color that Whitten dragged across the surface of the canvas to reveal streaks of colors layered below, like bark peeling from a tree. The exhibition then shifts to a tight, coherent series of black-and-white canvases that explore Euclidian geometry—the so-called Greek alphabet paintings from the late 1970s. A small gallery is devoted to works made in the 1980s, showcasing black-and-white paintings with richly encrusted paint in syncopated, irregular grid patterns formed by pushing paint through metal grates, screens, and other perforated objects. The concluding galleries are dedicated to the mosaic paintings that Whitten has produced since the 1990s and continues to develop today. Often referred to as memorial paintings, their titles honor individuals he admires, such as the musicians Miles Davis, Betty Carter, and Bobby Short, writer Ralph Ellison, congresswoman Barbara Jordan, and fellow artist friends Norman Lewis, Harvey Quaytman, and Alan Shields. In addition to the overarching commitment to formal experimentation, Whitten’s reuse of titles connects these seemingly divergent decades of work. Titles repeatedly refer to the artist’s hometown of Bessemer or pay homage to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., whom Whitten once met at a church in Montgomery, Alabama, after playing in the marching band at a Tuskegee/Alabama State football game.

It is in the gallery of slab paintings from the early 1970s that Whitten first deploys his formal experimentation to commanding effect. Whitten made this body of work by removing his own hand and paintbrushes from the canvas, instead dragging acrylic paint across densely built-up surfaces using afro combs and various homemade tools he calls “developers” fashioned from rakes, rubber squeegees, carpenter saws, and two-by-four pieces of lumber. This experimentation occurred well before Gerhard Richter began using a homemade squeegee to produce his iconic, blurry abstractions in the mid-1980s. Whitten’s Pink Psyche Queen (1973) serves as an apogee of this perceptual and conceptual body of process-based painting. The artwork offers a striking synthesis of addition and negation, creation and destruction, control and chance, rigor and freedom. And the triangular outline near the center of the painting hints at Whitten’s strong interest in geometry, which is expressed more fully in his next series, the Greek alphabet paintings from the second half of the decade.

In many respects, MCASD’s gallery configuration is less than ideal for monographic shows. The Whitten retrospective opens in a relatively cramped, vestibule-like space, and visitors frequently have to backtrack through the galleries. Robert Venturi’s Axline Court does a disservice to Whitten’s paintings with its dated, busy postmodern design of patterned terrazzo floors and distracting seven-pointed clerestory ceiling. However, in a gallery directly overlooking the Pacific Ocean, natural light bathes Sandbox: For the Children of Sandy Hook Elementary School (2013), enhancing one of the exhibition’s most elegiac and moving works. Installed alone on a wall, the large piece features acrylic objects embedded in the painting in a loose seven-by-ten grid configuration. The candy-colored objects suggest melted playground toys, and the natural La Jolla light makes them look like trapped plastic jewels, leading to disturbing associations between random violence perpetrated against children and the treatment of children like disposable trash.

Economists have coined the term “silver tsunami” to describe the aging baby boomer–filled workforce in the United States. But in many ways this term could also be applied to the current phenomenon of significant black artists in their seventies receiving major museum exhibitions. The timing of Whitten’s retrospective in La Jolla coincides with important exhibitions in 2014 and 2015 of Barbara Chase-Riboud (organized by Carlos Basualdo and John Vick at the Philadelphia Museum of Art), Senga Nengudi (organized by Nora Burnett Abrams at the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver), Mel Edwards (organized by Catherine Craft at the Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas), and Frank Bowling (organized by Gavin Delahunty at the Dallas Museum of Art.) Whitten, Chase-Riboud, Edwards, and Bowling all had work in the exhibition Witness: Art and Civil Rights in the Sixties, organized by Teresa A. Carbone and Kellie Jones for the Brooklyn Museum in 2014. Additionally, Whitten’s Sorcerer’s Apprentice (1974) was prominently featured in the Whitney Museum’s inaugural collection installation, America Is Hard to See, in its new building, a nod to the fact that the former curator Marcia Tucker gave Whitten his first solo show in the Whitney’s Lobby Gallery in 1974. (Interestingly, the Whitney also hosted the first museum presentation of Mel Edwards’s work in 1970.) It is gratifying to see so many distinguished artists receive the curatorial attention they deserve. The surge of these monographic exhibitions is also arguably the result of ground laid by recent group exhibitions, such as Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960–1980 (click here for review), curated by Kellie Jones in 2011 for the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles; and High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting, 1967–1975, an exhibition organized by Katy Siegel in consultation with the painter David Reed, which toured from 2006 to 2008. These group shows and monographic presentations illuminate the significant impact of curatorial work in recuperating artists’ careers and legacies.

Although the exhibition catalogue was lamentably not available during the run of the show in La Jolla, the museum did a somewhat unusual thing by offering visitors a take-away sheet of Whitten’s observations on painting, in his own words. Whitten’s statement is informed by the kind of wisdom that comes from a life marked by being born in the segregated south, on the one hand, and being part of a rewarding creative community in New York, on the other. It also sheds light on some of the threads connecting his multifaceted practice and the larger role that art plays in his life:

Experimentation with materials is my primary motivation to get up in the morning and go to the studio. Through experimentation I’ve discovered the most amazing things: I have discovered identity, I have discovered a truly modern concept of space, I have discovered a rhythm that keeps me in step with the cosmos and allows me to dance. Historical binary structures are the serious flaw in our evolution; binary thinking has disrupted out potential for spiritual fulfillment. Art provides a gap, a chance to stop, slow down and recuperate. Art as a process of healing offers a chance to restructure our sense of being.

Veronica Roberts

Curator, Modern and Contemporary Art, Blanton Museum of Art, The University of Texas at Austin