- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

Widely celebrated in the United States during the 1950s, Italian artist Alberto Burri (1915–1995) was subsequently forgotten. Forgotten by U.S. institutions, at least, as the nation solidified its claim as the cultural center in the era of Pop. Not so in Italy, where his place in the twentieth century as a key, postwar artist is now firmly established. In Rome, there is no shortage of catalogues to consult and exhibitions to visit. But in Los Angeles (or in English), many have never heard of him. Combustione: Alberto Burri and America, at the Santa Monica Museum of Art, sought to fill this lacuna by bringing the Italian artist back. Bringing him back, that is, to the city where he once lived.

Curated by Lisa Melandri and accompanied by a catalogue with essays by Melandri and Michael Duncan, the exhibition addressed the complex relationship that Burri had with the United States. A quick biography makes his ambivalence seem only natural. He began to paint while interned for nearly two years in a POW camp in Texas. He married American dancer Minsa Craig. He achieved great artistic success in the country that had once imprisoned him. And to top it all off, he purchased a house at 7423 Woodrow Wilson Drive, Los Angeles, where he spent nearly thirty winters, from 1963–1991. Hence the idea of the show: despite the fact that Burri considered himself an Umbrian artist—one who often expressed dislike for things American—the United States in general, and Los Angeles in particular, played a role in his artistic career that should be taken into account.

This exhibition was well worth a visit for those who are unfamiliar with the range of Burri’s work or for those who wish to consider his relationship to the United States more closely. Above all, regrouping an ensemble of works that have rarely come together recently in the United States (Burri’s last major retrospective here was in 1977), the show provided an opportunity to revisit a forgotten artist who merits wider appreciation.

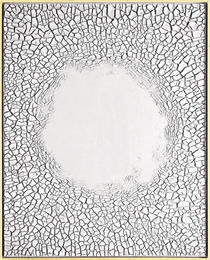

The exhibition included a compelling variety of works from 1951 to 1990, testimony to Burri’s perpetual innovation in both materials and processes. Although he is most well-known for his Sacchi—tableaux made by tearing, stitching, and painting burlap sacks—Burri never ceased to invent new manners of working on (nearly) two-dimensional surfaces. The Combustione (Combustions), made by burning paper, wood, or, later, plastic, achieve startling effects ranging from a ghostly figuration to baroque abstraction. Later, the Cretti (Cracks), paintings resembling a rectangular slice of a dried mud flat, manage to convey similar states of fissured materials through a dramatically different technique. The display was organized by grouping works of like processes in a roughly chronological sequence.

In many cases, chance played some part in making the final composition. His Cretti, whose physical process of drying produces networks of fissures across the surface, range from small (32.5 × 25.4 cm) to large (200 × 190 cm). Some of the ones on display take on surprisingly different forms depending on the manner in which Burri distributed the wet acrylic. Seeing them up close, the fissures look accidental; yet from a distance a clear composition always emerges, with an effect ranging the full gamut from the chaotic look of an all-over painting to abstract shapes hinting at primordial bodies. Unfortunately, Burri’s largest Cretto—and perhaps his most “contemporary” work—could not be moved for the show. This comes as no surprise, as Grande Cretto (1984–89) is a monumental Land art sculpture made by covering a destroyed Sicilian town with cement, laid thicker where buildings had stood and serving as an immense marker of a ruined past. This piece, as immobile as the ancient town had been, may be walked through like a monolithic maze or seen from an airplane.

While Burri offered sparse interpretation of his own works when he was alive, critics have described them in a wide range of manners. James Sweeney, director of the Guggenheim who championed Burri in the early 1950s, interpreted the re-sewn burlap as a postwar gesture toward the reparation of a torn humanity. Through metaphors of bodies and wounds, Burri is seen as repairing a world that is dysfunctional on a moral level. This view, drawing on the artist’s biography to support itself, was held widely during the period when Burri was first celebrated in the United States. Trained as a medical doctor, Burri renounced his profession while interned in Texas, famously proclaiming that he had seen too much destruction to continue healing. Other, more recent views of his work celebrate the tableaux as explorations into the materials of which they are composed, experiments that seek to understand the world of plasticity.

The catalogue for the show, a good introduction to Burri, presents further investigations of Burri’s relationship to the United States. The plates are organized by strict chronology, unlike the exhibition display. Duncan’s contribution assembles biographical clues, during the period from Burri’s time as a POW to his artistic rise in New York, suggesting that it was his return to the ruins of Renaissance Italy after the war that led him to rapidly adopt a new, radical abstraction. The essay is accompanied by previously unpublished photographs of Camp Hereford, Texas, where Burri’s unit was interned. Melandri’s article addresses the larger question of Burri’s relationship to the United States, suggesting that Los Angeles was more important to him than he was willing to admit. After all, the paintings he made while wintering in Los Angeles typically include “LA” in their titles, as Melandri notes. Similarly suggestive of a link to the American landscape, photographs taken by Burri—a prolific shutterbug—during trips to the Southwest show sweeping sand dunes, cracked mud, and curved hills, all forms that appear in his art as well. America certainly stood out for Burri as exceptional, but whether that uniqueness was positive or negative is hard to tell.

The catalogue is of generally high quality, yet a few of the color images, upon closer inspection, lack definition. Furthermore, the color plates are cropped tightly on the works, whereas it might have been better to include the frames, built by the artist as he self-consciously followed in the artisanal tradition of his Italian Renaissance predecessors. Rephotographing some of Burri’s pieces to include the frames might also have preserved a deeper three-dimensionality of the surfaces, many of which are alive with tangles of protrusions and recessions. Nonetheless, the careful research that went into the essays, both of which correct the historical record on various accounts, and the rich printing of most images make this exhibition catalogue an overall success.

Burri himself is often described as a strong personality, often difficult, and very opinionated. Later in life, as his fame in the United States diminished, he became increasingly frustrated with a historical record he saw as incorrect. In the story of the 1950s that Burri himself told, his works claimed primogeniture in establishing practices that later won fame for other artists. Indeed, as is discussed in the catalogue, one can see in his works a prefiguration of movements such as Gutai, Arte Povera, and Fluxus. Perhaps more directly, his early use of collage practices may have directly informed Robert Rauschenberg’s Combines following Rauschenberg’s visit to Burri’s Rome studio. If anything is clear, it is that his place in the art-historical story needs better accounting for.

In seeking a wider, not solely American, history of the postwar art revolution, the time seems appropriate for Burri to receive the American recognition that he felt he lacked later in his life and career. Or so suggested—in a convincing manner—this Santa Monica show. (Visitors who take particular interest in Burri’s work may eventually want to travel to the foundation that Burri established to house some of his most important pieces, located in the remote Città di Castello, Italy.) Yet, while the value of exhibiting Burri in Los Angeles seems clear, it is more difficult to judge whether the organizing principle of Combustione—Burri’s relationship to the United States—contributed to a fuller understanding of this artist, his work, or his historical importance. Biographically, it certainly makes sense to consider how his forced captivity and, later, adopted residence may have played a role in his life. This argument, found clearly in the catalogue, is not quite as convincing with regard to his practice, which seems to follow patterns established in Italy throughout the late 1940s and 1950s. Perhaps considering his Los Angeles work as some peculiar form of outsider art might allow us to see him as truly offering a different perspective. In this manner, we might begin to understand postwar, radical abstraction as something as Italian as it is American.

Eric Morrill

PhD candidate, Department of Visual Studies, University of California at Irvine