- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

“. . . this slumber of forgetfulness will not last forever. After the darkness has been dispelled, our grandsons will be able to walk back into the pure radiance of the past.” (Petrarch, Africa, IX, 453–7, quoted by Erwin Panofsky, Renaissance and Renascences in Western Art, New York: Westview Press, 1960, 10)

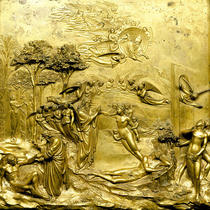

Petrarch’s concluding words to his epic poem Africa are equally applicable to Ghiberti studies. Long under the dark shadows of Richard Krautheimer and John Pope-Hennessy, Lorenzo Ghiberti and his magnificent Gates of Paradise from the Florentine Baptistery are finally being seen in a new light with fresh eyes. Free of corrosive deposits and later varnishes, the gilded bronze doors now appear much as they did at their installation in 1452, allowing us to witness Ghiberti’s breathtaking skill as a metallurgist, sculptor, storyteller, and goldsmith and to share the astonishment of Renaissance viewers like Michelangelo Buonarroti and Giorgio Vasari, who claimed them to be “the most beautiful work which has ever been seen in the world, whether ancient or modern” (quoted in the catalogue, 38).

The Gates of Paradise: Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Renaissance Masterpiece, organized by Atlanta’s High Museum of Art in collaboration with the Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore and the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence, Italy, and also exhibited in Chicago, New York, and Seattle, provides a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for U.S. audiences to experience Ghiberti’s genius intimately and be among the first to enjoy their newly revealed gilt surfaces. Mounted to celebrate the completion of a twenty-five year conservation, this extraordinary loan of three narrative panels and four framing elements has also occasioned a thoughtful and highly readable catalogue and a stimulating symposium that hopefully will free us from old, outdated, and untenable readings of Ghiberti’s career and impact on early Renaissance art.

As is well known, after beating out Filippo Brunelleschi, Jacopo della Quercia, and other sculptors in 1401/2 to create a second set of bronze doors depicting the Life of Christ for the Florentine Baptistery, in 1424 Lorenzo Ghiberti was awarded, competition free, another commission to create a third pair, with scenes from the Old Testament. These would ultimately displace Ghiberti’s first doors to the north façade, taking the prestigious opening on the eastern flank opposite the cathedral. Unlike the framework designed by Andrea Pisano in 1330 and adopted for the Life of Christ doors, Ghiberti radically changed the scheme to accommodate ten larger fields (approximately 31 1/2-inches square) for his Old Testament narratives. Worked in varying depths of relief—from subtle incisions to almost fully rounded figures—Ghiberti explored and expanded the utility of linear perspective to create believable, atmospheric, and deep settings for his biblical dramas. Their naturalism is heightened by exquisite attention to pose, gesture, expression, and decorative detail, much of which came during the chasing phase, thus revealing Ghiberti’s expertise in cold-working of the metal and mastery of surface detail surely derived from his experience as a goldsmith.

Three narrative panels, all taken from the left door, appear in the show: Adam and Eve, the first panel in the series; Jacob and Esau, perhaps the most well-known and fifth in the series; and David and Goliath from the lowest register, ninth in the series. These are interesting, albeit unexplained, choices, for they allow viewers to compare Ghiberti’s display strategies for reliefs meant to be seen from below and from above. Each panel relies on continuous narrative to convey its story, as characters appear several times throughout Ghiberti’s deep spatial settings. Most impressive is the quality of their newly revealed metal surfaces, which allow even the most expert viewer to see the panels as if for the first time. Close inspection is richly rewarded with Ghiberti’s seemingly infinite array of naturalistic and decorative details.

Most exciting, if perplexing, are the delicate and poignant gestures, expressions, and naturalistic details of the Adam and Eve panel. As Edilberto Formigli demonstrates in his catalogue essay on Ghiberti’s chasing techniques (119–33), the widest variety of decorative punches appear, as expected, in the four lowest panels, thus raising questions about the refinement of Adam and Eve. Indeed, who was meant to see the shiny scales of the serpent’s belly, the individual wings of the owls and falcons perched in Eden’s trees, or the salamanders creeping along the river bank near the newly created Adam? These miniscule details, intended for display at a height of at least fifteen feet, confirm the sincerity of Ghiberti’s claim that he “made this work with the greatest diligence and the greatest love” (17). Andrew Butterfield offers an interesting explanation, speculating that Ghiberti may have chased this panel himself to provide the standard and benchmark for the remaining nine, thus guiding his many assistants and ensuring the panels’ consistent quality (39). While the naturalistic delights of Adam and Eve may have been all but invisible after installation, there is no doubt that the scene’s emotional impact was well understood from below. Butterfield is correct to praise “the extraordinary subtlety with which Ghiberti described the mental, emotional, and physical states of the figures” (31); and his catalogue essay, much of which was adapted for the exhibition’s wall texts and audio guide, rehabilitates Ghiberti’s role as progenitor of the new naturalism associated with the early Renaissance.

With the Jacob and Esau panel, visitors can investigate Ghiberti’s inventive manipulation of one-point linear perspective and explore his mastery of human emotion. Ghiberti rose to the challenge of this complex multi-scene narrative with well-crafted figure groups that convincingly show joy, grief, jealousy, confusion, betrayal, humility, and acceptance. Visitors can marvel over exquisitely rendered locks of hair, tufts of animal fur, liquid drapery folds, and creased human flesh. David and Goliath offers the full range of Ghiberti’s chasing techniques, replete with small- and medium-sized circle punches, rosettes, stars, half-moons, and cross-hatching. Ghiberti’s debt to classical antiquity is also clearly on view here, once again showing old interpretations of the sculptor as “Gothic” to be without merit.

In New York, the exhibition was set up in the Metropolitan’s Vélez Blanco Patio (1506–15), chosen for its later Italian Renaissance ornament and its proximity to a gallery of small Italian bronzes. The three narrative panels stood in hermetically sealed, nitrogen-filled cases along a diagonal axis in the center of the room, with a life-size facsimile of the entire portal rising behind them. Oddly, one only learns about the replica’s dimensions in the accompanying audio guide, an important detail that visitors without headphones puzzled over. Also disturbing was the uneven focus of the photograph, in which the narratives are clear but the framework is blurred. With each panel raised on a podium at eye level, visitors have the remarkable opportunity to inspect Ghiberti’s craftsmanship up close and from multiple angles, including the exciting chance to view them in profile and from the back. Though never seen this way except in Ghiberti’s shop, such perspectives allow a fascinating glimpse at Ghiberti’s working process, further discussed on wall labels, in the audio guide, and in the accompanying catalogue. This display would have benefited from additional object labels for the panels’ backsides, thoroughly illustrated and explained in the catalogue but rather confusing to the exhibition visitor.

By necessity a small show, Atlanta and Chicago chose to supplement these selections with an illustrated timeline of the Baptistery’s construction and decoration, two interactive computer kiosks, documentary video footage of the restoration, and a reconstruction of Ghiberti’s wax model for the Jacob and Esau panel by Francesca Bewer, which she created during her investigations of Ghiberti’s casting technique (157–76, fig. 8.18). Unfortunately, these didactic materials were absent in New York, even though the patio’s western corners, as well as the area designated for a gift shop, could have accommodated some, if not all, of these elements. The wax model and conservation video were especially missed. The former because it provided a view into the debate, argued in two opposing catalogue essays, over whether Ghiberti used a direct or indirect method of casting. The video offered an important record and explanation of the complex and innovative restoration techniques devised for this project. Happily, all but the wax model are once again on view in Seattle.

A small portion of Ghiberti’s magnificent frame is also on view, represented by two standing prophets and two busts: one cleaned pair from the left frame’s upper corner adjacent to the Adam and Eve, the other still awaiting restoration, from next to Jacob and Esau. This presentation allows direct comparison of the metal surface before and after cleaning, clearly showing how Ghiberti’s masterpiece had become blackened and encrusted with corrosive deposits and varnish. The Metropolitan’s display, both for the framing elements and the narratives, would have benefited from the shaded diagrams of the doors used in Atlanta and Chicago, which allowed viewers to easily locate each element’s original placement.

Despite these minor alterations from venue to venue, the exhibition has been a resounding success with almost half a million visitors to date, not including Seattle’s attendance figures. The pieces will return to Florence in late April where they will be installed at the Museo dell’Opera di Santa Maria del Fiore in a special, hermetically sealed and climate-controlled display case, which has been designed to accommodate the reassembled doors while protecting them from further atmospheric damage. As Annamaria Giusti notes in the catalogue, this high-tech display “will nonetheless hardly compensate for the ‘disappearance’ of the Gates from the site for which they were originally conceived and . . . were displayed for centuries” (107). Though indeed regrettable, such precautions will ensure that Ghiberti’s brilliance will shine forth for many generations to come, thus allowing our grandchildren a splendid and radiant view of the past.

[To read Anne Leader’s review of a symposium accompanying the exhibition, click here.]

Numerous people helped me to write my reviews of the Ghiberti exhibitions. From the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, I would like to acknowledge Emily Beard, Communications Assistant, and Gary Radke, Consulting Curator of Italian Art; from the Art Institute of Chicago, Chai Lee, Public Affairs; from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Egle Zygas, Senior Press Officer; and from the Seattle Art Museum, Calandra Childers, PR, and Chiyo Ishikawa, Susan Brotman Deputy Director for Art, Curator of European Painting & Sculpture. These colleagues provided me with press kits, label information, installation and object photographs, attendance information, and the exhibition catalogue.

Anne Leader

Editor, IASblog, Italian Art Society