- Chronology

- Before 1500 BCE

- 1500 BCE to 500 BCE

- 500 BCE to 500 CE

- Sixth to Tenth Century

- Eleventh to Fourteenth Century

- Fifteenth Century

- Sixteenth Century

- Seventeenth Century

- Eighteenth Century

- Nineteenth Century

- Twentieth Century

- Twenty-first Century

- Geographic Area

- Africa

- Caribbean

- Central America

- Central and North Asia

- East Asia

- North America

- Northern Europe

- Oceania/Australia

- South America

- South Asia/South East Asia

- Southern Europe and Mediterranean

- West Asia

- Subject, Genre, Media, Artistic Practice

- Aesthetics

- African American/African Diaspora

- Ancient Egyptian/Near Eastern Art

- Ancient Greek/Roman Art

- Architectural History/Urbanism/Historic Preservation

- Art Education/Pedagogy/Art Therapy

- Art of the Ancient Americas

- Artistic Practice/Creativity

- Asian American/Asian Diaspora

- Ceramics/Metals/Fiber Arts/Glass

- Colonial and Modern Latin America

- Comparative

- Conceptual Art

- Decorative Arts

- Design History

- Digital Media/New Media/Web-Based Media

- Digital Scholarship/History

- Drawings/Prints/Work on Paper/Artistc Practice

- Fiber Arts and Textiles

- Film/Video/Animation

- Folk Art/Vernacular Art

- Genders/Sexualities/Feminisms

- Graphic/Industrial/Object Design

- Indigenous Peoples

- Installation/Environmental Art

- Islamic Art

- Latinx

- Material Culture

- Multimedia/Intermedia

- Museum Practice/Museum Studies/Curatorial Studies/Arts Administration

- Native American/First Nations

- Painting

- Patronage, Art Collecting

- Performance Art/Performance Studies/Public Practice

- Photography

- Politics/Economics

- Queer/Gay Art

- Race/Ethnicity

- Religion/Cosmology/Spirituality

- Sculpture

- Sound Art

- Survey

- Theory/Historiography/Methodology

- Visual Studies

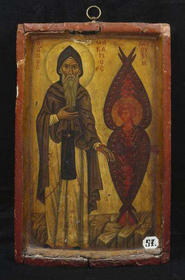

The greatest gift of the exhibition documented in this catalogue is exemplified by catalogue entry 44 (by Glenn Peers), a small panel of just two figures. The desert father Makarios stands to one side, straight and intensely decorous in the “angelic robe” of the monk, his right hand resting on his long beard, his left lightly raised. Beside him looms a seraph, its upswept wings echoing Makarios’s hood, its cherubic face intent. Gently, it takes the monk’s left wrist in its small, red hand. Monastic inspiration is distilled here in an image of penetrating simplicity. Previously published only once, the panel characterizes the icons that most distinguish this exhibition. Small, each one unique in its imagery, uncluttered visually but absorbing to view, they represent a kind of iconic content that has survived only in the hallowed spaces of monastic spirituality. Conspicuously lacking the big, blowsy Mothers of God and sour Pantokrators that haunt the traditional iconic repertoire, the collection assembled in Holy Image, Hallowed Ground opens a glimpse into a potent and special realm of visual meditation. To enter the space of these images is to enter a very particular contemplative environment, a “hallowed ground.”

The special selectivity of these images in the exhibition is addressed only visually—by being together—not by essays in the catalogue. The “hallowed ground” of its title refers instead to the awe-inspiring site of Mount Sinai itself. The monastery of St. Catherine located there preserves the greatest collection of Byzantine icons in the world. It does so because it was located in a remote site and absorbed into the Islamic sphere, where it was protected from Byzantine iconoclasm and was allowed to maintain its monastic practice unbroken since its foundation in the mid-sixth century. Isolated as it is, however, Sinai has also been a pilgrimage site throughout its history. The great gift of the catalogue is its visual presentation of this site, in its full-color reproductions of icons and artifacts, and in the outstanding evocation of the church and its stark, “God-trodden” setting in the catalogue’s opening chapter. Here, the focus of Robert Nelson’s attention is light, both natural light and candlelight. In words and photographs he follows the movement of light in both time and ritual, thus offering an analysis of a medium of immense importance in Orthodox Christianity’s sacred spaces that is all too rarely addressed. The theme of light recurs through the inclusion in the exhibition of two great candelabra and precious-metal altar fittings, including the great Sinai Cross.

The catalogue’s next two chapters consider the icon. Thomas Mathews sums up his groundbreaking recent research into the pagan roots of the early Byzantine panel-painted icon.1 Illustrated by fine color images, his chapter is the only one to survey panels from the monastery not as individuals but as a collection. He notes their small scale, individual themes, and votive character. His assessment is made on the basis of the early icons alone, but it rings vividly true for the later works in the exhibition and deserves emphasis.

The rich amalgam of inherited images and ongoing use that Sinai’s collection represents is exemplified in the third chapter by Father Justin Sinaites. Written by a member of Sinai’s own community, it treats the superb Codex Theodosianus, a Gospel lectionary of the late tenth century written entirely in beaded strokes of gold ink that are reproduced in close-up photographs of astonishing, tactile fidelity. Threaded with quotations from the Byzantine Fathers, the chapter is a beautiful meditation on the book as icon. So often our study of Byzantine icon theory finds a kind of grateful haven in likening the visual image to the word. Father Justin turns the formula around, likening the word to the image, and lodging the book in the realm of the icon, as the perceptible “body” of Christ veiling in sensory form a glory that can, like the transfigured Christ, blaze forth for those who understand. Nothing, Father Justin tells us, precludes the book’s full serviceability in the liturgy today. Juxtaposing the gleaming words for the feast day of the Transfiguration with the gleaming Christ of the Transfiguration mosaic at Sinai, he closes his chapter with a vivid evocation of the Codex Theodosianus itself held aloft in the liturgy at Sinai as Wisdom made visible. “Hallowed ground” assumes intense immediacy here.

The catalogue’s two final chapters study Sinai’s history as a pilgrimage destination. David Jacoby’s invaluable inquiry into Sinai travelers—who went, when, in what numbers, and by what routes—shows the wide cultural diversity of Sinai’s community, both resident and transient, and the bedeviling gaps in its available history. European accounts from the fourteenth and nearly every year of the fifteenth century make it clear that western Europeans were among Sinai’s steady visitors then; but how about in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries? This is the most prolific period for the icons at Sinai, and many have been associated with Latin patronage. Yet evidence of Latin presence there is strangely thin, and Jacoby urges us not to neglect the centuries-long testimony to east Christian pilgrims—Byzantine, Armenian, Georgian, Coptic, Syrian, Arabic. The challenge of sorting out Sinai’s diversity plays through the individual catalogue entries: Georgi Parpulov assigns a group of very accomplished early thirteenth-century icons to a Byzantine painter or painters—on whom one eagerly awaits further publication—while Rebecca Corrie defends a Melkite attribution for the famous bilateral icon of SS Sergios and Bakkhos, and Bissera Pentcheva proposes a (too?) daring Latin attribution for the mosaic icon of the Mother of God on the basis of the inspired suggestion that Latin patrons favored the Dexiokratousa posture because of the intimate closure of its Mother-Child relationship.

Sinai’s diversity plays strongly into the final chapter by Kristen Collins on how the topographic and deeply scriptural site of Sinai became wedded to the relic cult of St. Catherine. Collins aligns Sinai’s icons to show two significant shifts in its identity. One, rooted already in the twelfth century, is a slow adaptation of the Mother of God to refer to the site of Sinai. The monastery stands at the site associated with the burning bush; a figure of Mary in the “Kyriotissa” posture becomes recurrent on Sinai icons and is eventually labeled “tes Vatou”: of the bush. Soon thereafter, in the thirteenth century, Mary is entwined with branches and flames. Without earlier parallel in Byzantium or the West, this image must, Collins emphasizes, be a creation of Sinai itself. By way first of a label and then of a distinctive image, the monastery invented a way of portraying itself as a holy site. At much the same time, the depiction of St. Catherine became frequent. The thirteenth century, then, saw a fundamental realignment in Sinai’s image and its very identity. While Collins’s interpretation of the burning bush, emphasizing Mary’s purity rather than the Incarnation as such, imposes a Latin inflection not necessarily required by the iconography, Collins’s evidence is provocative. What precipitated this coupled shift in the imagery of Sinai? Indeed, what provoked the need to portray itself as a site? The proximity of the Crusader States and the later prominence of western European pilgrims invite us to link the shift with the Latin presence, but like the image of the burning bush itself, it cannot be explained by influence from the West alone. It must emerge from a distinctive and intricate local chemistry. The exhibition concluded with a number of icons that depict Sinai itself, initially through its holy figures but later through its landscape. The shift to landscape is not examined in the catalogue’s text but must have addressed shifting perceptions by eastern and western pilgrims alike of its “hallowed ground.” One awaits eagerly the work of younger scholars like Vessela Anguelova, who are studying the emergence of the icon of the holy place.

The catalogue documents, as it says, “the first exhibition devoted specifically to Sinai as a collection and a historical phenomenon” (xi). In the course of its five chapters, Sinai’s “hallowed ground” acquires different meanings. Nelson outlines three: holy image, holy place, and holy space. Holy space, he says, is represented by the church. Many of the exhibited icons come from the church, and due diligence was done in the exhibition to show the alignment of major icons around the templon screen. In the catalogue the “hallowed ground” of the church takes a compelling place in Nelson’s chapter. Holy place, in turn, is Sinai itself, addressed historically as a pilgrimage site, and represented in the many icons depicting its site. The catalogue investigates the changing holy figures that give identity to the site; the shift from figure to landscape as an image of its “hallowed ground” is largely left to the eye, surely representational for many viewers, and perhaps provocative for a few who wonder how the image of Sinai found its way from saint to landscape, from face to place. The most elusive of the three is holy image. The exceptional character of this exhibition, which defines it above all as coming from Sinai, lies in its many small icons with unusual compositions that condense saturated content into images of luminous simplicity. The distinctive character of this selection was not described in the catalogue; vision alone invites viewers into the “hallowed ground” between image and eye that is sanctified by such works. This review celebrates above all the sensitivity of the curators who selected those images, stood back from the temptation to talk about them too much, and reproduced them so well in the catalogue.

Annemarie Weyl Carr

University Distinguished Professor of Art History, Southern Methodist University

1 See especially Thomas F. Mathews, The Clash of God: A Reinterpretation of Early Christian Art, rev. ed. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999), 177–90; and Thomas F. Mathews and Norman Muller, “Isis and Mary in Early Icons,” in Images of the Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium, ed. M. Vassilake (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2005), 3–11.